Nov 11, 2015

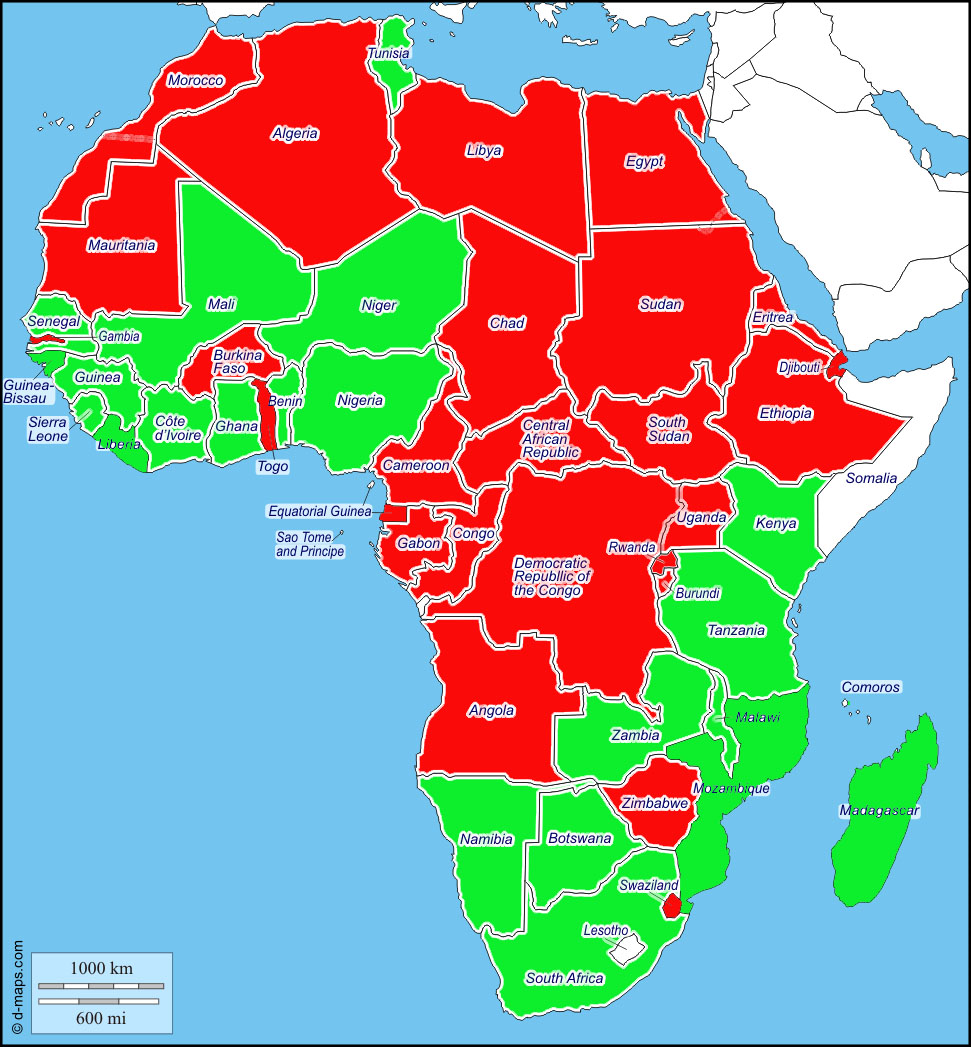

Africa's Dictators Fight BackAs these long-time autocrats left office there was genuine hope that Africa would shake off the dictatorship that had dogged the continent since Independence. For many years thereafter, the democrats seemed to be in the ascendancy and the dictators on the retreat, perhaps irretrievably so. Two-term limits were imposed on the Presidency in many African countries specifically to counter any tendency towards dictatorship. After legalizing political parties in Ghana in 1992, former military ruler Jerry Rawlings served two terms as civilian president before stepping down in 2000. In Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo stepped down at the end of his second term in 2007 after a failed attempt to alter the Nigerian Constitution to allow a third term. In Sierra Leone, Ahmed Tejan Kabba stepped down in 2007 after serving two terms in office and handed power over to current President, Ernest Bai Koroma. In Senegal in 2012 Abdoulaye Wade lost a third-term election bid by a wide margin after changing the Senegalese Constitution, amid street protests, to allow it. As late as 2014, the dictators' retreat appeared to be turning into a rout. Blaise Compaore, in power since 1987, fled Burkina Faso following popular protests over his proposal to amend the Constitution to remove the Presidential two-term limit.

Throughout this period, there was a feeling that the two-term Presidential limit was in Africa to stay, and democracy would

eventually prevail everywhere. Suddenly, Africa's dictators are

fighting back. Africa observers were surprised when an ECOWAS Heads of

State meeting in May, 2015 this year was unable

to agree on a proposal

to formalize the two-term limit as policy among all ECOWAS members.

Opposition reportedly came from two states, Gambia and Togo, which do

not have term limits for their Presidency. The need for consensus thus

forced ECOWAS policy to be dictated by two of its smallest members,

despite the fact that a clear majority of the ECOWAS countries do in

fact currently follow democratic practice (see map).

eventually prevail everywhere. Suddenly, Africa's dictators are

fighting back. Africa observers were surprised when an ECOWAS Heads of

State meeting in May, 2015 this year was unable

to agree on a proposal

to formalize the two-term limit as policy among all ECOWAS members.

Opposition reportedly came from two states, Gambia and Togo, which do

not have term limits for their Presidency. The need for consensus thus

forced ECOWAS policy to be dictated by two of its smallest members,

despite the fact that a clear majority of the ECOWAS countries do in

fact currently follow democratic practice (see map).

Suddenly in 2015 Africa, the two-term Presidential principle appears to be under attack. Sierra Leone President Ernest Koroma, under the two-term limit due to leave office in 2017, is rumoured to be considering a constitutional amendment to allow him to remain in office following a resolution by the ruling party Youth League calling for "more time" for him. In April this year, Faure Gnassingbe, successor as President to his father, Gnassingbe Eyadema, won election to a third term as President of Togo. In July this year, Pierre Nkururnziza was announced elected to a third term as President of Burundi even though the Burundi Constitution limits Presidents to two terms. And then just last month, a referendum amending the two-term limit in the Congo, Brazzaville, Constitution passed with an announced 92% in favour, clearing the way for President Denis Sasso-Nguesso to run for a third term in 2016.

Under "normal" circumstances, these arguments are not without merit. But the relatively young democracies of Africa have shown that they are fatally drawn to dictatorship. The precise reasons for this would provide rich ground for further study, but we would humbly suggest that it has something to do with the African "big man" syndrome, the traditional reverence for age and the widespread institution of chieftaincy. Rooted in tradition, Africa has a hard time escaping its past.

Modern management theory teaches that one of the key roles of the leader is building a competent leadership team. The benefits of having a strong, capable leadership cadre would seem obviously to outweigh the benefits of a single capable leader. However competent a leader might be, one way or the other he will eventually leave office, and without a strong structure to follow him, deterioration and/or outright collapse is inevitable. There is perhaps no better recent example of this than Ivory Coast, where Houphouet-Boigny ruled for decades over a relatively prosperous nation that quidkly collapsed upon his passing. There is also an unquantifiable benefit for national stability in having an ex-leader or ex-leaders, having left office peacefully, available in-country to offer advice and help keep the peace. Sierra Leone currently has no statesman of this nature, former Vice-President Solomon Berewa being the closest. Other countries such as Tanzania have several, and are the more stable for it.