7/5/2019

Notes

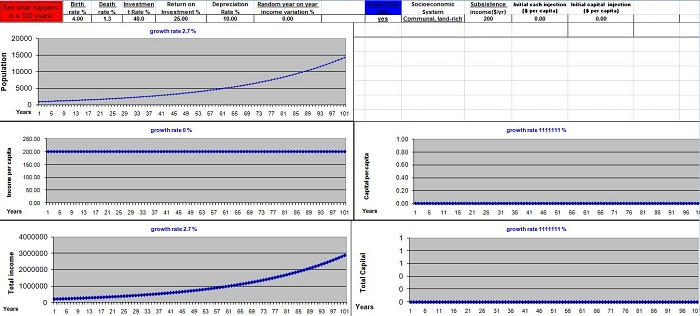

on The Development GameThe growth of population, total income, income per capita, total capital investment and capital investment per capita are charted, providing a dramatic illustration of our imaginary village's progress over a 100-year period. The Development Game does not predict the future. Obviously, population growth rates and the other key indicators depend on many factors, and can and do change with time in real-life situations. What the model does do, however, is calculate what direction our village is headed if the user-selected conditions were to remain constant. The Development Game focusses on capital investments as the means of economic growth. In the rural African setting there are other means to achieve economic growth: improved planting and soil management techniques, improved seed varieties, increased use of fertilizer etc. These do not necessarily involve capital equipment investments. However, by definition, the farmer without capital equipment is assumed to be at subsistence, whatever dollar level that may be. The Development Game assumes that these other growth opportunities are held constant during the period under analysis.

At subsistence, by definition, no internal

investment is possible

and the Development Game reveals the condition is self-promulgating.

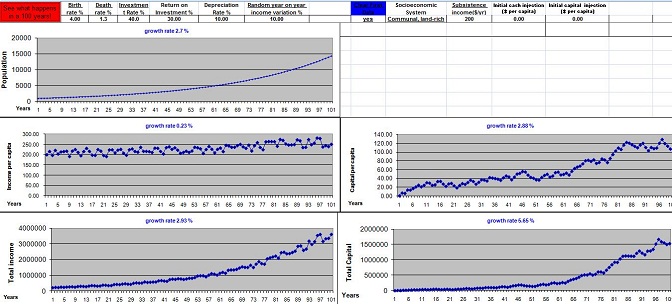

However, provision is made in the program for

random year-to-year

variations in income, which could occur due to a variety of factors in cluding weather, disease, war and

even government assistance. Thus

income can be made to vary plus and minus around subsistence. A random

drop in

income from subsistence leads unfortunately to hunger, malnutrition and

even death, but with an increase in income under the right, possibly

onerous, internal conditions of investment rate, return on investment,

population growth rate and depreciation rate, our villagers can lift

themselves (ever so slowly!) off subsistence and ultimately out of

poverty.

cluding weather, disease, war and

even government assistance. Thus

income can be made to vary plus and minus around subsistence. A random

drop in

income from subsistence leads unfortunately to hunger, malnutrition and

even death, but with an increase in income under the right, possibly

onerous, internal conditions of investment rate, return on investment,

population growth rate and depreciation rate, our villagers can lift

themselves (ever so slowly!) off subsistence and ultimately out of

poverty.

As populations increase, land scarcity can become a

problem. The

Development Game assumes that our village starts life with an abundance

of land, and even as populations increase there is sufficient land for

all.

The Development Game does not claim to model, even on a miniature

scale, national economies. For one no provision is made for government

influence in the economy. Our village's communal nature implies that

all inhabitants have more or less the same economic conditions, very

much unlike real-life situations in most African national economies.

However, use could be made of national indicators in determining

indicators for our village. For instance, it might not be unreasonable

to base birth rates for our village on those actually measured by

census authorities at the

national level.

And although The Development Game makes no claim to represent

national

economies, one can readily find instances where it demonstrates what

economists have told us about the basic prerequisites for national

development. Rapid population growth, we have often heard, can be

harmful to economic development. Run the game with the right indicators

and you

will see all the graphs trending upwards over a hundred years. Leave

all other indicators unchanged and increase birth rate by just

1%, and with the miracle (in this case perhaps the curse!) of

compounding the percapita graphs trend smartly downwards.

The Development Game vividly demonstrates the difference between per

capita trends and total trends. In many scenarios per capita income

trends downwards even as total income rises with a rising population.

This is analogous to many African economies, where the economy,

measured by GNP, is allegedly growing even as per capita incomes

stagnate or fall.

The Development Game implies that absent the internal

prerequisites for

economic grow th, aid and one-off external

capital investments are

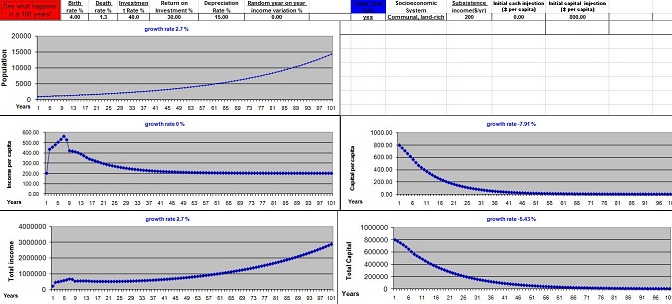

ultimately doomed. Assume a windfall capital infusion to our village

and give it starting capital equipment of 800 USD per capita, say. 100 years

later, absent

internal conditions for growth you find capital equipment whittled by

depreciation down

to zero and our poor villagers back at subsistence.The behaviour during the first few years, as the initial capital is consumed over the depreciation period, is interesting. Per capita incomes rise sharply in the year of capital injection and continue to rise throughout the depreciation period. This is followed by a sharp fall as the initial capital equipment is written off, and subsequent declines.

This may help to explain why well-meaning

assistance to African agriculture from national governments and partners often ultimately is not successful.

th, aid and one-off external

capital investments are

ultimately doomed. Assume a windfall capital infusion to our village

and give it starting capital equipment of 800 USD per capita, say. 100 years

later, absent

internal conditions for growth you find capital equipment whittled by

depreciation down

to zero and our poor villagers back at subsistence.The behaviour during the first few years, as the initial capital is consumed over the depreciation period, is interesting. Per capita incomes rise sharply in the year of capital injection and continue to rise throughout the depreciation period. This is followed by a sharp fall as the initial capital equipment is written off, and subsequent declines.

This may help to explain why well-meaning

assistance to African agriculture from national governments and partners often ultimately is not successful.

The effects of population growth on per capita economic growth in national economies has been the subject of great debate over the years. High population growth (especially in low income countries) and low population growth (especially in high income countries) have both been lambasted by different economic experts. Those economists who favour population growth postulate among other things that "as the country's population grows, the size of its potential market expands as well. The expansion of the market, in its turn, encourages entrepreneurs to set up new businesses." Thus, in this scenario, population growth itself increases the investment rate leading to increased per capita income. The Development Game does not address at all this debate among economists. Our simple model assumes the investment rate (and the other indicators used) are independent of population growth and constant over the period studied and addresses the question of what the outcome would be. It assumes for the period under review a small, land-rich agricultural economy at or near subsistence with no access to external capital. This reflects the situation in many African villages today.

In practical situations, the investment rate could be influenced by several factors, particularly, as far as our model is concerned, by per capita incomes. Starting from subsistence, when by definition investment is zero, in real life the ability and willingness to make capital investments increases as incomes increase. Studies show that wealthy farmers in the US, for example, can invest as much as 80% of their annual incomes on their farms. The balance 20% spent on consumption is still sufficient for them to live comfortably. The Development Game is not concerned with these exceptional (for Africa) situations. The focus here is on the critical region around subsistence, and the conditions necessary to escape it. The assumption of an investment rate uninfluenced by income levels is valid within sufficiently small income level ranges. Outside this small range the actual situation would be such as to increase the effect shown by The Development Game within the range. In other words, if the Development Game shows per capita incomes rising, in practice incomes would rise even faster to the extent that the actual investment rate increases with the rise in per capita income. And the reverse is true. If The Development Game shows per capita incomes falling, in practice incomes would fall even faster due to the effect of falling incomes on investment rate. This dependence of investment rate on per capita income could be incorporated into the game at some future date.

Looked at in this light, and plugging in reasonable numbers for the indicators, it quickly becomes evident that per capita income growth is not easy to achieve. The theory accords with extensive experience in Africa over the last 60 years! At subsistence, internal investment is zero by definition, and growth is impossible. In the region close to subsistence, the key investment rate indicator is likely to be low, inhibiting prospects for growth. Is our village doomed then to subsistence? Can nothing be done to change these hopeless prospects? How then have others escaped the self-propagating pit of subsistence? After all, the equations apply not just to Africa but much more generally, to all similar communities all over the world and over the centuries. How did they manage to grow? The argument has been made that a principal mechanism for building the capital to escape subsistence was slavery and its variants. Plantation slaves were a form of capital, odious as this was, steadily built up over the years, and later replaced by investments in capital equipment that could only have been possible through the earnings from slave labour. Thus slavery not only allowed the building of capital, but its abolition provided the impetus for the development of capital equipment. In other jurisdictions, conquest and plunder served the same purpose. We are straying far off the thrust of these notes, but suffice it to say that the peaceful, communal systems we are attempting to model here are the antithesis of slavery.

There are perhaps some dim rays of hope in an apparently dismal African outlook. As mentioned earlier, the Development Game focusses on investments in capital equipment and ignores so-called human capital development, so this is one area where the model and the practice might make gains. Some economists have focussed on population control as a key to third world economic gains; China for many years adopted a one-child policy that brought its population growth rate down, with great effort, by less than 1% in the thirty-five years of the policy from 1980 (albeit from already relatively low levels following previous birth control efforts). But the Development Game shows that reductions in the depreciation rate can have a greater effect than similar decreases in the population growth rate. Improvements in the depreciation rate might be easier to achieve and of considerably greater magnitude than changes in the population growth rate. A poorly-maintained vehicle might last 5 years (20% depreciation) whilst a patiently-maintained one might last more than 20 years (5% depreciation). Thus, a careful program to identify and procure cost-effective farm equipment, provision of spare parts possibly including local manufacture, and training of an army of farm equipment technicians might reduce the depreciation rate by several percentage points, far more than could be achieved with population control measures.

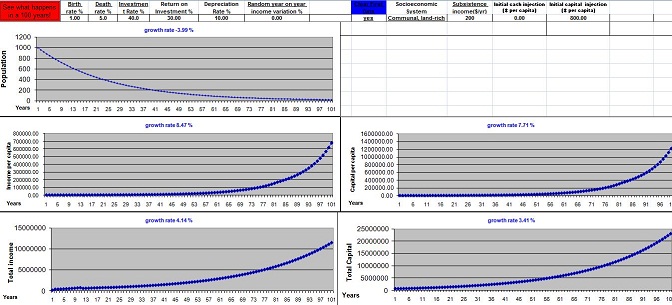

Certainly results from the Development Game need to be

analyzed

and

corroborated. Certainly some results will be unrealistic, especially at

the boundaries of normal human experience. If you set our village on a

path to extinction by making the death rate higher than the birth rate, strange results can ensue if people expire faster than capital, and the

capital per capita rises to astronomical levels. Before the demise our

last remaining villagers become fantastically wealthy. Capital

equipment of course requires human control, so the reality would be

somewhat different!

strange results can ensue if people expire faster than capital, and the

capital per capita rises to astronomical levels. Before the demise our

last remaining villagers become fantastically wealthy. Capital

equipment of course requires human control, so the reality would be

somewhat different!

The Development Game uses basic economic indicators and simple mathematical relationships to develop its trends. Although the African village situation was the focus of attention, the underlying indicators and maths have wider applicability. The game could be modified and extended to more closely fit real-life experience.

The Development Game uses basic economic indicators and simple mathematical relationships to develop its trends. Although the African village situation was the focus of attention, the underlying indicators and maths have wider applicability. The game could be modified and extended to more closely fit real-life experience.

- Free Download of The Development Game (name and email required) MS Excel required

- More Specifics on The

Development Game

- Contact us for comments and suggestions on The Development Game