From Sierra Leone Studies, No.

21, July, 1967

Kabala--The Northern Frontier Town(part 1)

By Milton Harvey,

Department of Geography, Fourah Bay College

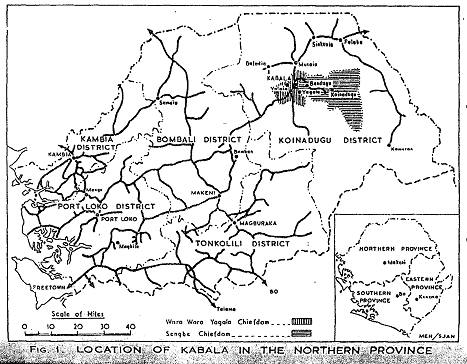

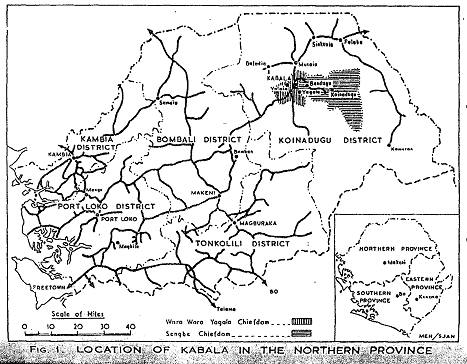

THE northern section of Sierra

Leone was until recently a region of

conflict between the different ethnic groups of the area. In spite of

this, there was an appreciable amount of trade between the upper Niger

basin and the north-western coast of present day Sierra Leone.

Actually, in the middle of the nineteenth century, "trading caravans

travelled from Timbuktu, Bamako, Segou, Kankan and other centres

bringing local produce (and collecting more on the way) with which to

trade and barter at the coastal towns and factories".1 The

intermediate collecting centres were Falaba, Musaia, Samaia and Bumban;

whereas the coastal towns and factories included Kambia, Mange, Port

Loko, and Magbile. At that time, there was either no settlement called

Kabala, or it was a small unimportant village not worth visiting by

traders. Even as late as 1895, a year before the proclamation of the

Protectorate over the hinterland of Sierra Leone, Kabala was not shown

on Cardew's map of the country’s internal trade routes.2

He distinguished only four major routes. The first was from Falaba

either via Bafodia through Karene to Port Loko, or via Koinadugu

through Bumban to Port Loko. The second one was from Mototoka through

Loko territory to Benkia on the Rokel River From Benkia, the goods were

transported to Magbile (lower down the river) in dug-outs, and then in

larger boats to Freetown. The third route, Cardew noted, linked

Freetown to Mongeri through Senehun. The last was related to the then

ports of Bonthe, Lavana, Sulima and Mano Salija.

The atmosphere of political unrest in the north did not seem to have had a very adverse effect on normal trade. But this continuous latent state of war, however, considerably influenced the siting of individual centres and the general pattern of settlement. Most places were either perched on inaccessible hill tops (Yataia, Falaba), or sited in easily defensive saddles and valleys (Kabala, Koinadugu, Sinkunia). Usually, the natural defences were improved by encompassing the settlement by ditches and mounds. Cotton trees were even planted round places for the same reason. Tree-ring villages in the north are very prominent on air photographs of this area.

The relative decline of Falaba, Musaia and Sinkunia, flourishing commercial and administrative centres about 1825, was due to two main factors. Firstly, the ‘Sofa Wars’ of the 1880’s not only seriously affected the caravan trade between the Niger basin and the north-western coast of Sierra Leone, but also resulted in the

1 P. K. Mitchell, “Trade Routes of the Early Sierra Leone Protectorate”, Sierra Leone Studies, (June 1962), p. 204.

2 Cardew’s map is reproduced by P. K. Mitchell, Ibid., between pages 212 and 213.

burning down of these centres. Secondly, the importance of the towns as marketing and commercial centres was greatly reduced when the boundary between Guinea and Sierra Leone was established on 21st January, 1895. On the delimitation of this boundary the trade of the Niger basin was diverted by the French to Conakry. Without a prosperous hinterland Falaba, Musaia and Sinkunia gradually declined. Decay of these more northern centres was paralleled by a corresponding rise in the importance of Kabala. As a result of this, the frontier post was transferred from Falaba to Kabala in 1896, and by the 1st December, 1897, Kabala had become the headquarters of the Koinadugu District, the other districts being

Karene, Ronietta, Panguma and Bandajuma. Kabala

is now the most important settlement in the extreme north of the

country. Actually, it has also become the medical, educational and

commercial centre for the whole of Koinadugu District. But due to its

isolation from other large urban centres and because of poor

communication, markets for its agricultural products—tomatoes,

cabbages, and ground nuts—are limited.

other districts being

Karene, Ronietta, Panguma and Bandajuma. Kabala

is now the most important settlement in the extreme north of the

country. Actually, it has also become the medical, educational and

commercial centre for the whole of Koinadugu District. But due to its

isolation from other large urban centres and because of poor

communication, markets for its agricultural products—tomatoes,

cabbages, and ground nuts—are limited.

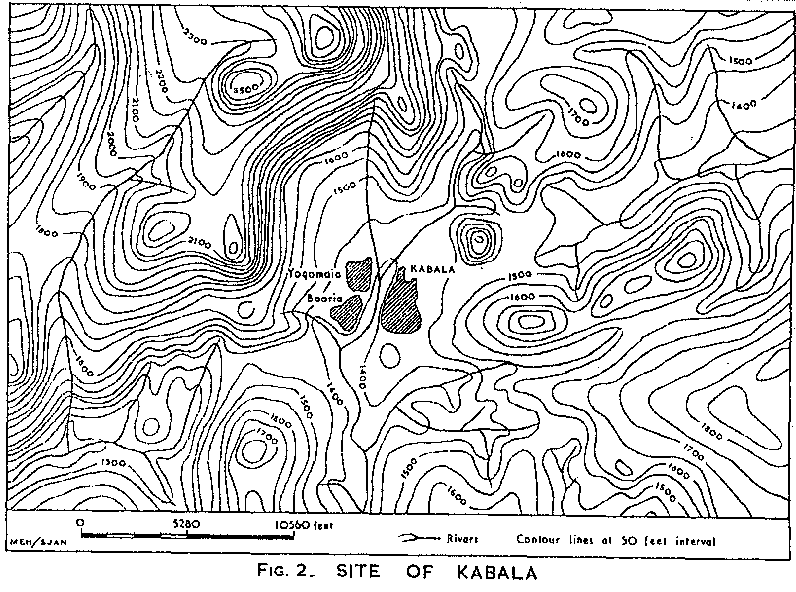

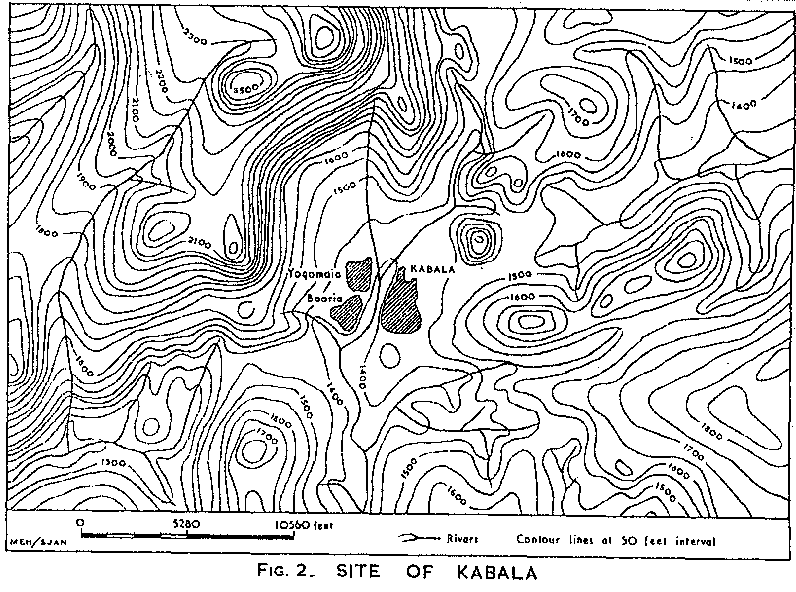

Situated mainly between the 1,500 and 1,550 feet contour, Kabala is "ensconced in its cradle of hills ". These ranges which trend either north-north-east to west-south-west or east-north-east to south (Fig. 2) usually culminate in bare steep-faced peaks called inselbergs. It was in this cradle of hills that Kabala was nurtured, and the gaps between the hills became natural routeways to the town. Thus the physical conditions of the site assisted in the emergence of the town as a nodal centre important for commerce and services.

Kabala however has some site

disadvantages Being located

almost at the centre of a centripetal drainage system, all the streams

either near or within the town are very small, heavily colonized by

aquatic plants and in the dry season their flow is intermittent. In

addition the mountainous nature of the area considerably reduces

potential agricultural land. Thus, around the town, peasant farming is

mainly concentrated in the valleys where villagers grow tomatoes,

cabbages, and peppers. On the whole, this part of the country is more

suitable for the rearing of cattle.

Kabala however has some site

disadvantages Being located

almost at the centre of a centripetal drainage system, all the streams

either near or within the town are very small, heavily colonized by

aquatic plants and in the dry season their flow is intermittent. In

addition the mountainous nature of the area considerably reduces

potential agricultural land. Thus, around the town, peasant farming is

mainly concentrated in the valleys where villagers grow tomatoes,

cabbages, and peppers. On the whole, this part of the country is more

suitable for the rearing of cattle.

Because of the negative relief features of the area, the scarcity of water, and the pattern of human activity, settlements are on the whole nucleated, and temporary Fula cattle settlements may be the only examples of dispersed settlement.

Morphological and Demographic Growth

Many towns in Sierra Leone (e.g. Magburaka, Kenema,

Sefadu) grew from a single nucleus, but a few, such as Bo, Makeni and

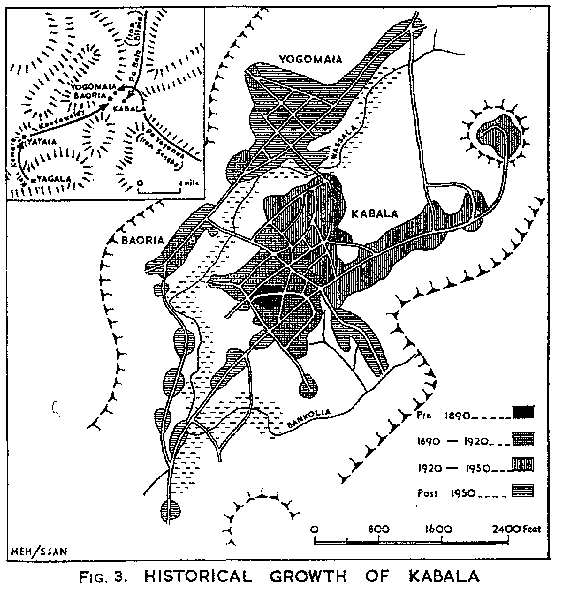

Taiama, developed from more than one nucleus. Kabala, however, does not

seem to fit into any of these groups, for a unicellular growth in the

first instance was replaced by a multicellular one based on three

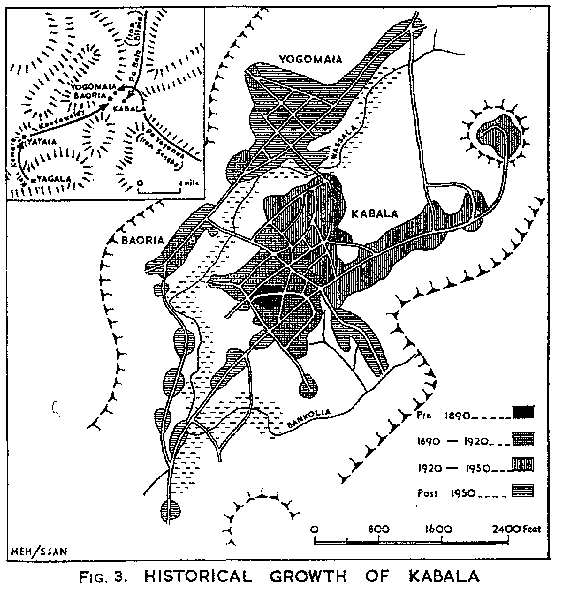

nuclei — Yogomaia, Baoria and Kabala (Fig. 3).

The precise date for the founding of Kabala is not known. However, it is probable that Kabala was not founded before 1820, for Laing, who knew the area reasonably well, makes no mention of its existence. Perhaps the first mention of Kabala, in historical records was in connection with Windwood Reade’s visit to Falaba in 1869. Reade "arrived intending to explore the Sherbro, but he decided instead to follow Laing’s example, make for Falaba, and seek the source of the Niger. With help from Governor Kennedy, he set out early in 1869 via Port Loko, Bumban and Kabala ".3 Even as late as 1895, the settlement was so unimportant that it was bypassed by Cardew’s four internal trade routes of the country. Somewhere, therefore, between 1820 and 1895, local tradition states that a Koranko hunter and tobacco grower called Pa Bala, founded the nucleus of present day Kabala. Formerly, Bala lived

3 C. Fyfe, A History of Sierra Leone (O.U.P., 1962), p. 367

in Bitaia, a Koranko village destroyed during the Sofa raids. But because of certain family disputes and competition from other tobacco growers, he decided to leave Bitaia and founded an independent village where he could continue growing his tobacco for sale to the Limba. To ensure the success of his venture and to ascertain the best possible site for his village, he went to a sorcerer who told him that a favourite grazing ground for guinea-pigs was the most ideal. After a period of intensive search, Bala finally found such a site and built a few huts for his family. This settlement was called by the Limba, Ka Bala, that is, Bala’s village. In Limba "Yaundo Kai Ka Bala" means "I am going to Pa Bala’s ". To improve the natural defences of

the area, cotton trees, similar to those round Falaba, Musaia and

Sinkunia, were planted round the settlement (Fig. 3). Kabala was then a

small village mainly composed of members of Bala’s extended family.

To improve the natural defences of

the area, cotton trees, similar to those round Falaba, Musaia and

Sinkunia, were planted round the settlement (Fig. 3). Kabala was then a

small village mainly composed of members of Bala’s extended family.

After the Sofa wars and the destruction of Falaba, and other more northerly centres, Kabala was chosen as the headquarters of administration in the north in 1897. A District Commissioner, Mr. C. E. Birch, and a detachment of the Frontier Police were stationed in the village. The Barracks of the Court Messengers (as the Frontier Police were later called) were west of the hunter’s settlement along the main Falaba road. Since these Barracks were in the Wara Wara Yagala chiefdom, the government asked the chief of that area, Pa Koko, resident at Yagala, to send a representative to Kabala. This man, who was to act as regent, was to be responsible for the implementation of government laws, such as the obligation to collect the hut tax. Actually, he was to act as a liaison between colonial and traditional life and to help introduce the former. The first regent, Kele Karnara, did not live in Kabala but resided at the village of Yataia, about two miles from the Barracks (Fig. 3). This Limba village had a “peculiarity that walls of houses are built of stone instead of mud. Instead of being due to some old traditions, this may have originated in shortage of clay up there, an abundance of loose stones and absence of water to mix clay “.4

The absence of good road-links between the hill-top settlement of Yataia and Kabala resulted in administrative delays. Therefore, when Pa Lamina became chief of Wara Wara Yagala in 1909, his regent, Pa Kondowulay, founded a new settlement, Baoria, about half a mile from Kabala. This village was detached from Kabala and the barracks by swamps and the Wassala stream. At the time of the founding of Baoria, the population of Kabala must have increased because of the Court Messengers and their families.

During the regentship of Kele Kamara. history repeated itself for a Pa Yogomah after quarrelling with his brother, the chief of Sengbe, fled from Koinadugu, the headquarters. Since he was declared a persona non grata in his area, he went to seek protection from Kele Kamara of Yataia. The regent, as a sign of friendship, gave Yogomah land north-west of Kabala but separated from it by the Wassala stream. The settlement founded by this Koranko became known as Yogomaia—the place of Pa Yogomah.

Although it is difficult to date accurately the founding of Yogomaia, it is certain that it was in existence by 1908 when Kondowulay succeeded Kale Kamara as regent. By 1910, therefore, Baoria and Yogomaia were permanent villages. In that year, the Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone observed that there was "space for camping between Kaballa (Kabala) and Yorgoma (Yogomaia) for at least a brigade in the dry weather ".5 Of the three villages, only Kabala was sizeable. Including the Barracks, it had 104 houses, about 624 inhabitants. These

4 F. W. H. Migeod, A View of Sierra Leone, (Kegan Paul, Trench, and Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1926), pp. 59-60.

5 Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone (Vol. II., Routes, 1910), p. 39.

6 Ibid., p. 156.

buildings included 12 traders’ shops and 40 houses for the Court Messengers. Functionally, Kabala was even at that time an administrative, commercial and medical centre for the Koinadugu District. It had a resident District Commissioner, a Medical Officer and 30 Court Messengers. Furthermore, there was a market and 12 shops. The population of Kabala increased considerably because of rural- urban migration reflecting the medical and commercial importance of the settlement. Finally, the increased population offered an assured market for the agricultural products of the area.

During the First World War, Kabala continued to grow because it was a recruiting centre for soldier; commerce therefore correspondingly increased. Thus for 1920, Kabala had grown to engulf the Barracks, while Baoria and Yogomaia had grown very little.

During the 1920-1950 period, Yogomaia and Baoria experienced only slight population increases. Kabala, on the other hand, continued to grow because of the combination of many factors. Firstly the construction of a road in 1922 linking the town to Falaba must have resulted in increased commercial activity and some population increase. More important, however, was the opening of the Makeni-Kabala motor road in 1930. Kabala therefore became an important communication town, and its status as a collecting centre was considerably enhanced.

Secondly, with the building of primary schools around the same time, there was a large influx of children from the rural areas, and Kabala’s population grew. In 1929, for example, it had a population, including the Barracks, of l,005.8

Thirdly, the increase in trade, especially in cattle, after 1930, coupled with the expansion of the hospital and an increase in the administrative staff, encouraged migrations from the rural areas. Even Baoria and Yogomaia experienced some population increase. By the end of the Second World War, Kabala’s commercial section consisted of shops owned by both Lebanese and Africans. There were, however, no European commercial firms in the town. In 1947, the total population of Kabala, Yogomaia and Baoria was estimated at 3,064.9

Up to 1950, Kabala’s expansion was mainly eastwards because westward growth was inhibited by secret society forest, and in the north, the Wassala stream was an important limiting factor to the town’s growth.

By the end of 1950, Kabala was a large settlement which dwarfed Yogomaia and Baoria; it was bounded in the west by forest, in the north by the Wassala stream, and in the east and south by mountains. These physical factors had great influence on the town’s subsequent growth. After 1950, the construction of good roads to join the three settlements encouraged the growth of

7 Ibid., p. 49.

8 Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone, (1930), p. 58.

9 From tax returns, 1947.

Baoria and Yogomaia sections—people working in Kabala may now stay in these sections without any great mobility problems. Yogomaia, however, has shown a greater rate of growth than Baoria (Fig. 3), partly because of the large influx of Fula both from the surrounding country, and from Guinea. Growth in the Kabala section has mainly been in the form of interstitial infilling and ribbon development along the main roads, notably the Makeni road. The three settlements have now fused both morphologically, through ribbon development and increased intra-urban mobility, and functionally—Baoria is the seat of the chief; Kabala is the commercial centre and the base for district administration. The 1963 Census showed that the three settlements had a total population of 4,610. The word, Kabala, is now used to mean all three settlements. In spite of this fusion, physical influences are still important agents dictating the siting of buildings, and influencing the shape of the urban unit.

Although Kabala’s population seems to have shown a continuous increase its growth rate has not been very striking. Between 1927 and 1963, the town’s population increased by l,040.9%, whereas that of Koidu increased by 11,193.0%. Kabala’s development was initially due to its frontier position; and because of the then remoteness of the north, it became the centre of commerce and trade.

The inception of peace in the country coincided with the gradual evolution of a road-rail network. As trade increased considerably, the reasons for town growth in the country changed; productivity of the hinterland, accessibility to other sections of Sierra Leone, and the availability of services superseded defence; the Police replaced the Court Messengers. Consequently, though Kabala is still growing, centres like Makeni, Magburaka and Lunsar are growing at a faster rate and Kabala is continuously being pushed down the hierarchy of settlements in the country. From being the ninth largest town in 1946, it became the twenty-first in 1963.

The atmosphere of political unrest in the north did not seem to have had a very adverse effect on normal trade. But this continuous latent state of war, however, considerably influenced the siting of individual centres and the general pattern of settlement. Most places were either perched on inaccessible hill tops (Yataia, Falaba), or sited in easily defensive saddles and valleys (Kabala, Koinadugu, Sinkunia). Usually, the natural defences were improved by encompassing the settlement by ditches and mounds. Cotton trees were even planted round places for the same reason. Tree-ring villages in the north are very prominent on air photographs of this area.

The relative decline of Falaba, Musaia and Sinkunia, flourishing commercial and administrative centres about 1825, was due to two main factors. Firstly, the ‘Sofa Wars’ of the 1880’s not only seriously affected the caravan trade between the Niger basin and the north-western coast of Sierra Leone, but also resulted in the

1 P. K. Mitchell, “Trade Routes of the Early Sierra Leone Protectorate”, Sierra Leone Studies, (June 1962), p. 204.

2 Cardew’s map is reproduced by P. K. Mitchell, Ibid., between pages 212 and 213.

burning down of these centres. Secondly, the importance of the towns as marketing and commercial centres was greatly reduced when the boundary between Guinea and Sierra Leone was established on 21st January, 1895. On the delimitation of this boundary the trade of the Niger basin was diverted by the French to Conakry. Without a prosperous hinterland Falaba, Musaia and Sinkunia gradually declined. Decay of these more northern centres was paralleled by a corresponding rise in the importance of Kabala. As a result of this, the frontier post was transferred from Falaba to Kabala in 1896, and by the 1st December, 1897, Kabala had become the headquarters of the Koinadugu District, the

other districts being

Karene, Ronietta, Panguma and Bandajuma. Kabala

is now the most important settlement in the extreme north of the

country. Actually, it has also become the medical, educational and

commercial centre for the whole of Koinadugu District. But due to its

isolation from other large urban centres and because of poor

communication, markets for its agricultural products—tomatoes,

cabbages, and ground nuts—are limited.

other districts being

Karene, Ronietta, Panguma and Bandajuma. Kabala

is now the most important settlement in the extreme north of the

country. Actually, it has also become the medical, educational and

commercial centre for the whole of Koinadugu District. But due to its

isolation from other large urban centres and because of poor

communication, markets for its agricultural products—tomatoes,

cabbages, and ground nuts—are limited.Situated mainly between the 1,500 and 1,550 feet contour, Kabala is "ensconced in its cradle of hills ". These ranges which trend either north-north-east to west-south-west or east-north-east to south (Fig. 2) usually culminate in bare steep-faced peaks called inselbergs. It was in this cradle of hills that Kabala was nurtured, and the gaps between the hills became natural routeways to the town. Thus the physical conditions of the site assisted in the emergence of the town as a nodal centre important for commerce and services.

Kabala however has some site

disadvantages Being located

almost at the centre of a centripetal drainage system, all the streams

either near or within the town are very small, heavily colonized by

aquatic plants and in the dry season their flow is intermittent. In

addition the mountainous nature of the area considerably reduces

potential agricultural land. Thus, around the town, peasant farming is

mainly concentrated in the valleys where villagers grow tomatoes,

cabbages, and peppers. On the whole, this part of the country is more

suitable for the rearing of cattle.

Kabala however has some site

disadvantages Being located

almost at the centre of a centripetal drainage system, all the streams

either near or within the town are very small, heavily colonized by

aquatic plants and in the dry season their flow is intermittent. In

addition the mountainous nature of the area considerably reduces

potential agricultural land. Thus, around the town, peasant farming is

mainly concentrated in the valleys where villagers grow tomatoes,

cabbages, and peppers. On the whole, this part of the country is more

suitable for the rearing of cattle.Because of the negative relief features of the area, the scarcity of water, and the pattern of human activity, settlements are on the whole nucleated, and temporary Fula cattle settlements may be the only examples of dispersed settlement.

Morphological and Demographic Growth

The precise date for the founding of Kabala is not known. However, it is probable that Kabala was not founded before 1820, for Laing, who knew the area reasonably well, makes no mention of its existence. Perhaps the first mention of Kabala, in historical records was in connection with Windwood Reade’s visit to Falaba in 1869. Reade "arrived intending to explore the Sherbro, but he decided instead to follow Laing’s example, make for Falaba, and seek the source of the Niger. With help from Governor Kennedy, he set out early in 1869 via Port Loko, Bumban and Kabala ".3 Even as late as 1895, the settlement was so unimportant that it was bypassed by Cardew’s four internal trade routes of the country. Somewhere, therefore, between 1820 and 1895, local tradition states that a Koranko hunter and tobacco grower called Pa Bala, founded the nucleus of present day Kabala. Formerly, Bala lived

3 C. Fyfe, A History of Sierra Leone (O.U.P., 1962), p. 367

in Bitaia, a Koranko village destroyed during the Sofa raids. But because of certain family disputes and competition from other tobacco growers, he decided to leave Bitaia and founded an independent village where he could continue growing his tobacco for sale to the Limba. To ensure the success of his venture and to ascertain the best possible site for his village, he went to a sorcerer who told him that a favourite grazing ground for guinea-pigs was the most ideal. After a period of intensive search, Bala finally found such a site and built a few huts for his family. This settlement was called by the Limba, Ka Bala, that is, Bala’s village. In Limba "Yaundo Kai Ka Bala" means "I am going to Pa Bala’s ".

To improve the natural defences of

the area, cotton trees, similar to those round Falaba, Musaia and

Sinkunia, were planted round the settlement (Fig. 3). Kabala was then a

small village mainly composed of members of Bala’s extended family.

To improve the natural defences of

the area, cotton trees, similar to those round Falaba, Musaia and

Sinkunia, were planted round the settlement (Fig. 3). Kabala was then a

small village mainly composed of members of Bala’s extended family.After the Sofa wars and the destruction of Falaba, and other more northerly centres, Kabala was chosen as the headquarters of administration in the north in 1897. A District Commissioner, Mr. C. E. Birch, and a detachment of the Frontier Police were stationed in the village. The Barracks of the Court Messengers (as the Frontier Police were later called) were west of the hunter’s settlement along the main Falaba road. Since these Barracks were in the Wara Wara Yagala chiefdom, the government asked the chief of that area, Pa Koko, resident at Yagala, to send a representative to Kabala. This man, who was to act as regent, was to be responsible for the implementation of government laws, such as the obligation to collect the hut tax. Actually, he was to act as a liaison between colonial and traditional life and to help introduce the former. The first regent, Kele Karnara, did not live in Kabala but resided at the village of Yataia, about two miles from the Barracks (Fig. 3). This Limba village had a “peculiarity that walls of houses are built of stone instead of mud. Instead of being due to some old traditions, this may have originated in shortage of clay up there, an abundance of loose stones and absence of water to mix clay “.4

The absence of good road-links between the hill-top settlement of Yataia and Kabala resulted in administrative delays. Therefore, when Pa Lamina became chief of Wara Wara Yagala in 1909, his regent, Pa Kondowulay, founded a new settlement, Baoria, about half a mile from Kabala. This village was detached from Kabala and the barracks by swamps and the Wassala stream. At the time of the founding of Baoria, the population of Kabala must have increased because of the Court Messengers and their families.

During the regentship of Kele Kamara. history repeated itself for a Pa Yogomah after quarrelling with his brother, the chief of Sengbe, fled from Koinadugu, the headquarters. Since he was declared a persona non grata in his area, he went to seek protection from Kele Kamara of Yataia. The regent, as a sign of friendship, gave Yogomah land north-west of Kabala but separated from it by the Wassala stream. The settlement founded by this Koranko became known as Yogomaia—the place of Pa Yogomah.

Although it is difficult to date accurately the founding of Yogomaia, it is certain that it was in existence by 1908 when Kondowulay succeeded Kale Kamara as regent. By 1910, therefore, Baoria and Yogomaia were permanent villages. In that year, the Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone observed that there was "space for camping between Kaballa (Kabala) and Yorgoma (Yogomaia) for at least a brigade in the dry weather ".5 Of the three villages, only Kabala was sizeable. Including the Barracks, it had 104 houses, about 624 inhabitants. These

4 F. W. H. Migeod, A View of Sierra Leone, (Kegan Paul, Trench, and Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1926), pp. 59-60.

5 Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone (Vol. II., Routes, 1910), p. 39.

6 Ibid., p. 156.

buildings included 12 traders’ shops and 40 houses for the Court Messengers. Functionally, Kabala was even at that time an administrative, commercial and medical centre for the Koinadugu District. It had a resident District Commissioner, a Medical Officer and 30 Court Messengers. Furthermore, there was a market and 12 shops. The population of Kabala increased considerably because of rural- urban migration reflecting the medical and commercial importance of the settlement. Finally, the increased population offered an assured market for the agricultural products of the area.

During the First World War, Kabala continued to grow because it was a recruiting centre for soldier; commerce therefore correspondingly increased. Thus for 1920, Kabala had grown to engulf the Barracks, while Baoria and Yogomaia had grown very little.

During the 1920-1950 period, Yogomaia and Baoria experienced only slight population increases. Kabala, on the other hand, continued to grow because of the combination of many factors. Firstly the construction of a road in 1922 linking the town to Falaba must have resulted in increased commercial activity and some population increase. More important, however, was the opening of the Makeni-Kabala motor road in 1930. Kabala therefore became an important communication town, and its status as a collecting centre was considerably enhanced.

Secondly, with the building of primary schools around the same time, there was a large influx of children from the rural areas, and Kabala’s population grew. In 1929, for example, it had a population, including the Barracks, of l,005.8

Thirdly, the increase in trade, especially in cattle, after 1930, coupled with the expansion of the hospital and an increase in the administrative staff, encouraged migrations from the rural areas. Even Baoria and Yogomaia experienced some population increase. By the end of the Second World War, Kabala’s commercial section consisted of shops owned by both Lebanese and Africans. There were, however, no European commercial firms in the town. In 1947, the total population of Kabala, Yogomaia and Baoria was estimated at 3,064.9

Up to 1950, Kabala’s expansion was mainly eastwards because westward growth was inhibited by secret society forest, and in the north, the Wassala stream was an important limiting factor to the town’s growth.

By the end of 1950, Kabala was a large settlement which dwarfed Yogomaia and Baoria; it was bounded in the west by forest, in the north by the Wassala stream, and in the east and south by mountains. These physical factors had great influence on the town’s subsequent growth. After 1950, the construction of good roads to join the three settlements encouraged the growth of

7 Ibid., p. 49.

8 Military Report of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone, (1930), p. 58.

9 From tax returns, 1947.

Baoria and Yogomaia sections—people working in Kabala may now stay in these sections without any great mobility problems. Yogomaia, however, has shown a greater rate of growth than Baoria (Fig. 3), partly because of the large influx of Fula both from the surrounding country, and from Guinea. Growth in the Kabala section has mainly been in the form of interstitial infilling and ribbon development along the main roads, notably the Makeni road. The three settlements have now fused both morphologically, through ribbon development and increased intra-urban mobility, and functionally—Baoria is the seat of the chief; Kabala is the commercial centre and the base for district administration. The 1963 Census showed that the three settlements had a total population of 4,610. The word, Kabala, is now used to mean all three settlements. In spite of this fusion, physical influences are still important agents dictating the siting of buildings, and influencing the shape of the urban unit.

Although Kabala’s population seems to have shown a continuous increase its growth rate has not been very striking. Between 1927 and 1963, the town’s population increased by l,040.9%, whereas that of Koidu increased by 11,193.0%. Kabala’s development was initially due to its frontier position; and because of the then remoteness of the north, it became the centre of commerce and trade.

The inception of peace in the country coincided with the gradual evolution of a road-rail network. As trade increased considerably, the reasons for town growth in the country changed; productivity of the hinterland, accessibility to other sections of Sierra Leone, and the availability of services superseded defence; the Police replaced the Court Messengers. Consequently, though Kabala is still growing, centres like Makeni, Magburaka and Lunsar are growing at a faster rate and Kabala is continuously being pushed down the hierarchy of settlements in the country. From being the ninth largest town in 1946, it became the twenty-first in 1963.

....Forward to Part 2